Overview

This recreation of Lunar Lander was programmed in Easy68k assembly over the course of two weeks. It features two different win conditions, physics, and a seven-segment display.

Implementation

Rendering

Rendering was accomplished by reading in a BMP file and, using its file header, extracting the necessary data to calculate the width and height of the image. From there, each individual picture was read in and drawn to the screen. As this process is costly, only the areas of the screen that had movement on top of them needed to be rewritten. This drastically sped up the program.

determineColor

* Determine color

move.l (a0), d1 ; move next color from memory into pen

* Byte shift

ror.l #8,d1 ; make sure all the bytes are in the right spots

* If color is transparent, skip it

cmp.l #TRANSPARENT_COLOR, d1

beq skipDraw

* Set color and draw pixels

move.l #PEN_COLOR_TRAP_CODE, d0 ; set the proper trap code to set the pen color

trap #15 ; set pen color through trap code

* Set location to draw

move.l d3, d1 ; x location

move.l d4, d2 ; y location

move.l #DRAW_PIXEL_TRAP_CODE, d0 ; set trap code back to drawing pixels

trap #15 ; draw pixel

skipDraw:

* Loop incrementers

addi.l #1,d3 ; increment width counter

cmp.l d3,d5 ; compare loop counter (d1) to width (d5)

bne continueRow ; continue loop

nextRow:

move.l d7, d3 ; reset width counter for next loop

subi.l #1,d4 ; decrement height counter

move.l THIS_OFFSET_Y(sp), d1

cmp.l THIS_OFFSET_Y(sp), d4 ; check if height has reached offset

bne clipX ; if it has not, continue

* Return to caller

move.l #4, d0

sub.l d0, sp

jsr loadAllRegs ; restore registers

add.l d0, sp

rts ; return from function

Physics

Physics was implemented using simple linear acceleration.

* Params: direction x, direction y

* Positive x -> right, positive y -> down

addVelocity:

* Math

* Add x direction to velocity

move.l DIR_X(sp), d0 ; move var from stack to register

cmpi.l #0, d0 ; if x velocty is 0, don't use fuel

beq skipFuelX

subi.l #1, (fuel) ; subtract 1 from fuel

skipFuelX:

muls #ACCELERATION_X, d0 ; multiply acceleration by direction to get correct direction

add.l d0, (velocityX) ; add acceleration to velocity

* Add y direction to velocity

move.l DIR_Y(sp), d0 ; move var from stack to register

muls #ACCELERATION_Y, d0 ; multiply acceleration by direction to get correct direction

cmpi.l #0, d0

beq skipFuelY

subi.l #1, (fuel) ; subtract 1 from fuel

skipFuelY:

add.l d0, (velocityY) ; add acceleration to velocityThe challenging aspect of implementing it, however, was in converting integers to floats. x86 Assembly, storing only bytes of information, does not have any inherent method to represent floats. Instead, fractional bits were used. Essentially, depending on how accurate I wanted my float to be, n fractional bits were reserved as the last n bits of the longs I used. Then, any math could be applied to those drawn out numbers, and the fractional bits can be shifted back when the number needed to be used as an integer.

* Add velocity parameters

move.l #12, d1 ; set space for parameters

sub.l d1, sp ; set up SP

move.l d5, (sp) ; move values onto stack

move.l d4, 4(sp)

jsr addVelocity

* Get x result

move.l (velocityX), d5 ; move velocity into register

add.l d5, d6 ; add it to position

* Get y result

move.l (velocityY), d5

asr.l #FRAC_BITS, d5

asr.l #FRAC_BITS, d5 ; shift d5 back

add.l d5, d7 ; add y velocity to position

add.l d1, spWin Conditions

Two win conditions and one lose condition were present in the game. The player could safely land on yellow segment for 1 point or on the green segment for 2 points. If the player had a velocity above a certain amount when they landed or landed in a different area, they would die and be sent to the start of the game. Win conditions were calculated based on the color of the pixel directly below the lunar lander. If the hex code of the color matched one of the winning colors, the player would gain a point and return to the main menu.

checkForWin:

cmpi.l #WIN, (gameWon) ; if game was not won, it was lost

bne gameEndLose

gameEndWin:

* Check for extra points

cmpi.l #1, (extraPoints)

beq showExtraPtsScreen ; if extra point win, go to extra point screen

bra showWinScreen ; if regular win, go to regular win screen

gameEndLose:

jsr redrawBackground

jsr drawSpriteBroken ; draw broken sprite if lose

jsr swapBuffer

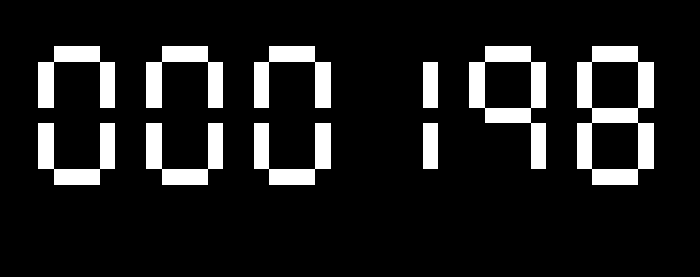

Seven Segment Display

A seven segment display has one main advantage over using sprites to represent numbers: it is a lot faster. Lines being drawn instead of entire images that needed to be read in before even beginning to be drawn shaves off a ton of time. For implementing this, I stored a table to show the coordinates of every line in a single digit based around the lower left corner. Figuring out exactly how I wanted to do that took a few attempts and more than a few sketches.

segmentTable:

dc.b $3F ;0

dc.b $06 ;1

dc.b $5B ;2

dc.b $CF ;3

dc.b $66 ;4

dc.b $6D ;5

dc.b $7D ;6

dc.b $07 ;7

dc.b $7F ;8

dc.b $67 ;9

ledPositionTable

dc.l $00010003 ; a = (1,0) -> (3,0)

dc.l $01040304 ; b = (4,1) -> (4,3)

dc.l $05040704 ; c = (4,5) -> (4,7)

dc.l $08010803 ; d = (1,8) -> (3,8)

dc.l $05000700 ; e = (0,5) -> (0,7)

dc.l $03000100 ; f = (0,1) -> (0,3)

dc.l $04010403 ; g = (1,4) -> (3,4)

Once I figured out how I wanted to store each of the lines, drawing them was deceptively easy. To get each digit by itself, I used x86’s version of modulus. Then I looped through each number, and each segment of each number. After that, I used x86’s trap code for drawing a line given two coordinates.